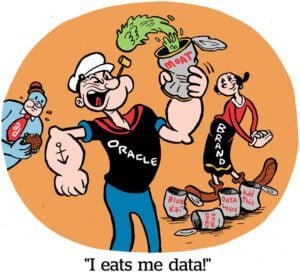

A recent trend of false advertising class-action suits has plagued the food and CPG industry.

The latest product in the hot seat is Poppi, a digital-native soda brand facing a class-action suit disputing its “prebiotic” and “gut healthy” marketing claims. According to the complaint, soda drinkers must consume four cans a day at least to gain any prebiotic benefits. Since it’s a sugary soda, those benefits would be offset by the sugar consumption.

But Poppi is far from an isolated example of allegedly false and deceptive food advertising, if the number of recent class-action suits is any indicator. Other examples include Liquid I.V., which was sued this year for claiming it has no preservatives, when it does contain citric acid and other preservatives. And cereal brand Three Wishes was sued for making allegedly misleading claims about protein. Apparently, the cereal includes some protein that isn’t digestible by the human gut – so people aren’t actually getting protein.

Part of the trend is a new form of food supply-chain activism.

For example, Ben & Jerry’s stopped describing its cows as “happy” after animal rights advocates sued in 2020. There was also a spate of around 50 or so spurious and opportunistic suits in 2020 and 2021 targeting numerous different brands arguing that the vanilla flavor in their products didn’t come from real vanilla beans or extract. (Many of those cases were later dismissed.)

But there is another potential contributing factor to the rise in litigiousness – and one that indicates we’ve so far only had a taste of the consumer backlash to mislabeled and misleading grocery products.

I refer to the expansion of online grocery and retail media.

The new retail aisle

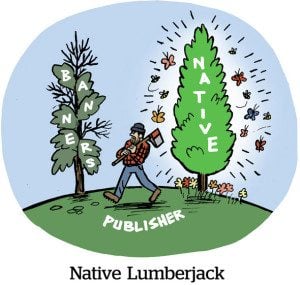

The phenomenon of food-related false advertising suits is being exacerbated by a new style of CPG brand and new media, where the rules over product claims are amorphous and unregulated. Retail media ads now extend to social media and affiliate content, as well as sponsored product listings in search feeds and across the web.

As an example, let’s look at Magic Spoon, the social-native cereal brand, which stopped describing itself as “vegan-friendly” last year after consumers raised concerns because it’s, well, simply not vegan. There’s dairy in it. But Magic Spoon still advertises itself as Keto-friendly – although a rigorous Keto dieter would no doubt be discouraged to learn that these cereals are not actually Keto. (Misleading a vegan into consuming dairy feels more effed up, though.)

But an influencer making unsupported and potentially false claims about a product can now sell directly into a retail media network with SKU-level specificity just as if they’d handed out a coupon in the store. A social creator can also make claims in a post that would not be countenanced on the product packaging itself or in any TV commercial.

There has been some regulation – like a self-regulatory enforcement warning the National Advertising Division issued last year, after Gatorade, a Pepsi-owned brand, complained about a social campaign sponsored by Coca-Cola’s Bodyarmor beverage in which Baker Mayfield, an NFL quarterback, used a barf face emoji to describe Gatorade flavors. For TV ads, associating a competitor with someone getting sick would be a clear no-go. On social media, it’s on the verge of “puffery,” the legal term for when businesses describe a product using hyperbolic or comic exaggeration not expected to be taken as reality (“World’s best pizza,” for instance).

Not to pick on Magic Spoon for what is a widespread problem, but language like “vegan-friendly” is a useful example. Lots of people are vegan-ish or purchase vegan products as a proxy for more sustainable and healthy food. That’s probably a strong audience for Magic Spoon.

Also, with ad platforms like Google and Meta, the emphasis nowadays is on “steering” campaigns. Including “vegan” or “vegan-friendly” in the product details and targeting parameters is likely a good way to steer those platforms to identify potential customers with vegan preferences.

But this practice can lead to awkward situations.

Consider the metadata packed into sponsored product listings and product pages. Is putting “vegan” as a search or metadata keyword the same as advertising a product as vegan? Not really – but the word “vegan” might even be highlighted if the metadata term is a direct match to the user’s search.

And it would be very easy to mislead someone into believing the product is vegan. False advertising litigators are actively on the lookout for potentially erroneously applied marketing terms like “gut healthy,” “nutritious” and “low sugar.”

Yet, a search for “vegan cereal” on Walmart’s site prompts a prominent page-top sponsored listing for … Magic Spoon.

To be fair, targeting “vegan” as a search term is not the same as making a claim that a product is vegan. But the convergence of online search and retail media, along with more US shoppers ordering groceries online, will lead to customer confusion – and very likely many more deceptive ad suits.