Closed-loop attribution is a marketer’s dream.

But the ease of measuring return on ad spend (ROAS) from placements on ecommerce sites is a “moral hazard,” said Stephen Howard-Sarin, managing director of retail media at Criteo, during Programmatic I/O’s first-ever Retail Media Summit on Monday.

“The hazard is that ROAS can flatten your strategy and turn everything into performance media when it shouldn’t always be,” Howard-Sarin said. “Once you have that simple, one-size-fits-all measurement of impact on sales, it takes a certain amount of discipline to not use it.”

Fixating on ROAS also makes it harder to figure out how certain parts of a campaign perform, especially now that retail media buys often include other, less performance-focused channels like display and CTV as audience extension.

Retail advertisers aren’t just dealing with fragmentation across retail media networks and inventory types. They’re grappling with how to make retail media fit together with all the different pieces of their campaigns.

And they’re learning that focusing too much on the bottom of the funnel can clog the whole system.

Performance isn’t everything

Even within retail media networks (RMNs), not all inventory is suited to direct sales, said Mara Greenwald, SVP of commerce media at Night Market, Horizon Media’s commerce agency.

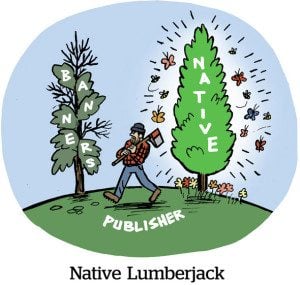

RMN campaigns almost always include on-site placements on a retailer’s website and app. But nowadays retail media spans off-site media on other publisher sites and apps, in-store placements, OOH and even audio, to name a few common components of the RMN media mix. Ad inventory varies between native product listings, traditional display formats and video placements.

Display and video are generally better suited for brand awareness campaigns than closed-loop ecommerce sales. However, display and video ultimately drive in-store and online conversions.

Marketers really need dedicated models for measuring incrementality across all of these channels, Greenwald said.

Focusing narrowly on retail attributed sales makes even less sense in the context of wider media buys that also include search, social, TV and other formats, she added. And the attributed sales metric can hinder a campaign’s potential to drive conversions across all of these media types.

“What we often find is that, when you optimize or measure on the media attributed ROAS, we’re not actually revving up holistic sales,” Greenwald said.

Plus, she said, focusing too much on ROAS optimization can limit the scale of programmatic campaigns, since high-ROAS inventory tends to be in limited supply.

The price of performance

Limited supply means higher prices. And pricing differentials across inventory types can also skew ROAS-based optimization efforts, said Ben Sylvan, VP of data partnerships at The Trade Desk.

For example, a buyer could be purchasing off-site media through an RMN that includes expensive CTV inventory from a major network like NBCU, as well as cheaper display inventory from non-retail digital publishers, Sylvan said. But if the buyer is measuring the ROAS of both inventory types using the same standards, they’ll be misled about the relative value of these inventory types.

“If you’re trying to bring new buyers to your brand, ROAS is probably not the right metric to measure against,” he said. “My concern is that people talk about [ROAS] as if it’s a catchall, but there’s nuance within every campaign objective.”

Sylvan added that, instead of loyalty only to ROAS measurement, advertisers should try household penetration or improving the reporting they see on new buyers and where those buyers are coming from.

But Greenwald cautioned against defaulting to any single measurement model or ROAS option. For example, some clients find that improving their share of voice in search results has the most impact on ecommerce sales, whereas share of voice doesn’t drive incremental sales for others, she said.

In other words, in a fragmented retail media marketplace, the best strategy just might be having many different strategies.