Digital media and marketing M&A is suffering from a prolonged case of anemia.

The cause? Uncertainty in the market.

It’s unclear whether inflation will return, interest rates will continue rising or if there may yet be a recession on the horizon. (The answer to that last one depends on who you ask.)

As a result, valuations were down in Q3 and so was overall digital media and marketing deal volume, according to LUMA’s most recent market report, released last week. It’s been the same story quarter over quarter for the past year.

Ad tech M&A activity, specifically, was relatively flat compared with Q2.

Efficiency FTW

But there were two large ad tech deals in Q3: Novacap’s $600 million acquisition of Cadent and DoubleVerify’s $125 million purchase of Scibids. Plus, a smattering of smaller acquisitions got tossed in for good measure, including iSpot nabbing 605 and Contentsquare’s agreement to buy Heap.

Although there isn’t an obvious theme that connects these deals on the surface, said LUMA Partner Conor McKenna, there is a through line of sorts, which is “an increasing focus on efficient growth rather than growth at all costs.”

DoubleVerify is a good example of this dynamic.

Although it’s down from its IPO price, its stock is up year to date as a reward from investors for focusing on the fundamentals. “They’ve had strong growth and profitability,” McKenna said. “Now they’re able to focus on where they want to go by making acquisitions.”

The Scibids deal is a continuation of DoubleVerify’s ongoing expansion over the past couple of years as it moves beyond measurement and into media activation and campaign optimization.

“As interest rates have gone up, valuations have come down, and companies big and small are spending more time thinking about improving their core business,” McKenna said. “Not only does that process take time, but different companies have different timelines in terms of when they feel like they’re on a secure enough footing to invest in the future and in big opportunities.”

Glass (maybe) half full

Meanwhile, despite a still-hovering cloud of uncertainty over the market, there is another potential bright spot (although perhaps not everyone would agree), which is optimism about ad spending.

Magna, GroupM and professional industry prognosticator Brian Wieser are all predicting growth in the ad market through Q4 and into next year. And 2024 has a few tricks up its sleeve, including the Summer Olympics and US presidential election, both of which are typically big drivers of advertising spend.

It’s also possible that advertisers will spend more programmatically in the moment than is reflected in these projections. Programmatic is relatively easy to turn on and off, and, if advertisers find they’re having a good Q4, they might up their spending.

“Even if advertisers are being cautious and holding back a little longer than they normally would, using programmatic and digitally enabled channels means that they’re able to turn the knobs closer to the point of execution,” McKenna said. “Everything we’re seeing and hearing is that Q4 is going to be quite strong.”

Line in the sand

Though looking beyond Q4, the year to come isn’t just any year.

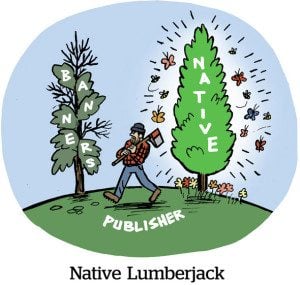

It’s also the year that third-party cookies will supposedly finally get the kibosh. And once the phaseout is complete, it could trigger some consolidation in the market.

The ad tech industry is in “a very weird situation,” McKenna said, in which it’s dealing with dual forms of uncertainty: the macroeconomic issues that everyone is facing and massive ecosystem-specific changes (namely, the end of third-party cookies).

That shoe is dropping, but it’s falling slowly.

In the interim, a lot of companies have cropped up claiming to have cookieless solutions and innovations to manage the industry’s data problems. These startups will likely be attractive acquisition targets, but only once third-party cookies really are gone.

The situation wasn’t all that different before GDPR went into effect in 2018. There wasn’t much ad tech deal activity until the elephant actually entered the room.

“In the 18 months leading up to GDPR, there wasn’t one scaled identity-focused deal, and then the summer after it went into effect, there were multiple,” McKenna said. “Things move less slowly when people get comfortable with what a situation looks like in reality.”